Posts in Category: My Reviews

Book Review: Galdrbok, Practial Heathen Runecraft, Shamanism & Magic

This is a partial book review of Galdrbok, Practical Heathen Runecraft, Shamanism, & Magic by Nathan J Johnson and Robert J Wallis.

This eloquent book attempts to recover our indigenous European shamanism known as the Northern Tradition, as practiced by our ancestors in the ancient Old North. It describes an initiatory system inspired by the spiritual legacy of Heathen communities of the Migration Age, dating from around 300 to 700 CE marking the transition from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages.

By mapping the altered conscious states which enable shamanic travel, including scrying (‘to descry’/‘foresee’/ crystal gaze), galdr (‘sung spells’), runic mediation, and other powerful techniques for entering ecstasy, it offers us access to the nine otherworlds of Yggdrasil, the Northwest European shamanic world tree. Thus we can learn how to walk between the nine worlds in the footsteps of Woden and Freyja, the Northern shamanic deities par excellence.

Galdrbok was recommended to me by one of the people involved in its research due to my interest in shamanism. After reading the introduction I was attracted to it because I realised that as a woman with a strong English heritage, I had an unmet need to connect with the shamanic practices of my ancient ancestors. School history lessons had led me to believe that the British Isles had been invaded so many times over thousands of years that our ancient cultural practices had been eroded out of existence. To the extent that as a teenager I noticed that contemporary Western culture presented Pagan practices such as crystal ball gazing, witchcraft, spell casting, and the use of herbs etc to the realm of fiction for entertainment purposes only.

Later in my adult life, after using many natural healing methods for my poor state of health, I had an appetite to research the history of shamanism. This led me to the work of Mircea Eliade, John G. Neihardt, Thomas E Mails, Carlos Castaneda, and Michael Harner, who in the twentieth century revealed that there are many indigenous cultures across Mother Earth still managing to hold onto their rich spiritual heritage and natural healing methods. They have done so successfully through direct oral teachings down the generations for thousands of years. As such they have some very well-tested methods for physical and mental healing accessed through altered states of consciousness through the use of psychedelic plant medicines and, more commonly, percussion sounds.

As a Shamanic Practitioner for the past four years I have been healing myself and others through a contemporary method of shamanic healing devised by my shamanic teacher, Scott Silverston who based it on the teachings he received from a Native American Shamaness in Arizona. It is similar to Harner’s Core-Shamanism in that it employs a rapid drumming beat to induce an altered state of consciousness to access Spirit Mind or Shamanic Consciousness to communicate with benevolent spirits for guidance and healing.

It wasn’t a lack of interest in ancient cultural practices from the British Isles that led me on this path, it was an interest in healing myself through spiritual practices that have been uncommon in contemporary Western society.

In their preface, the authors of Galdrbok are very dismissive about Neo-Shamanism, in particular, the work of Michael Harner:

Harner argues that ‘core shamanism’ is based on certain universal principles which can be disassociated from cultural contexts … we argue, in contrast, that Core-Shamanism is a Western ideal version of what is, in all of its examples worldwide, intrinsically culturally embedded.

This quote exhibits a lack of perspective about what Harner’s work has achieved. If we look at Neo-Shamanism as an empowering tool for Westerners to reconnect with Spirit and our Creator for much-needed healing, then the lack of cultural embeddedness is a moot point. It simply doesn’t matter whether or not the universal principles that form Core-Shamanism are disassociated from cultural contexts if they are effective tools for healing the huge amounts of trauma and abuse that remain unhealed in the West.

Since the Romans took control of Western spirituality through their invention of Christianity, Westerners have lacked any real connection with Father Sky and Mother Earth. Religion brought fear of God and embedded the notion that we are all sinners and intrinsically unworthy of God’s love. By removing the possibility for individuals to directly connect with Spirit in favour of a hierarchical priesthood, the result has been rampant egotism that expresses itself through a culture of consumerism, misuse of sex, competitiveness, greed, lust, and total lack of care about the Earth or her animals.

Harner’s work demonstrates that indigenous tribal cultures continued certain common shamanic practices during that time, ensuring the maintenance of their direct connection to Creator for healing and optimal wellbeing. In turn, Harner brought such teachings to wider awareness in his own country of America, arguably one of the most damaged societies on Earth. In this context, I see him as a modern saint who brought the gift of shamanic healing to the unhealed masses.

The authors of Galdrbok claim:

Many people find shamanism appealing because it is perceived to be a ‘personal’, ‘free’ and ‘eclectic’ spiritual path …. But the notion that it is free and eclectic is largely a Western Stereotype imposted on shamanism as we have universalised it and removed curltural diversity from it.

However, they do not cite any research to back up this claim, which makes it simply a sweeping statement of no value. In my informed opinion, I would say that the students of Harner and Ingerman are drawn to shamanism not as the authors say, but because it provides empowerment and a simple method of self-healing for those wishing to recover from the abuse and trauma so prevalent in our contemporary age.

Sandra Ingerman was a student of Harner and in her book ‘Soul Retrieval’ she describes how shamanic drumming enabled her to access healing for sexual abuse. I know a man whose wife never sought healing for the sexual abuse she had experienced as a teenager and the trauma caused her to become very narcissistic. Her behaviour towards him was abusive throughout his 20 loyal years with her before she finally drove him from the marriage. Had she been as motivated as Ingerman to heal her trauma it would not have been externalised and passed on to her husband and son.

Ingerman has revealed that she was initially afraid to follow the direction of her spirit guides to start writing her books. It was by working through her blocks she became empowered to write several as well as recording a drumming CD, deliver lectures, record regular podcasts, and set up several support groups. Through her dedicated work, she has brought the ability to self-heal through simple methods to a much wider audience.

Galdrbok certainly appears to be a well-researched, scholarly record of ancient magic and spirituality, and I’m looking forward to discovering if it can provide access to individual healing to the extent that Neo-Shamanism has over recent years.

I shall make further posts as I better understand what Heathen shamanism is and what the practical use of ancient rune magick can achieve for the contemporary individual.

I have started my journey by making my own set of runes and buying a crystal ball.

I prefer to buy in-print books directly from the author or independent bookshops. Sadly, this book is only available from Amazon online but you may be able to order it from your local independent bookshop:

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Galdrbok-Practical-Heathen-Runecraft-Shamanism/dp/0954960955

CleanTalk Anti-Spam Protection

This website was inundated with over 500 spam comments a week before I installed CleanTalk Anti-Spam. I hadn’t noticed until there were thousands of them waiting to be approved, and it took me hours to go through and delete them all. I looked through the available WordPress Plugins and found CleanTalk and decided to give it a go – and I’m so glad that I did. Now I get an email once a week with a summary of the items they have blocked for me, which is usually 4-500. Their software analyses the comments and blocks comments that are generated by Spam Bots.

Go here for more information on how they can help your website: https://cleantalk.org

Zen In The Art of Archery

Zen In The Art of Archery was recommended to me by the late Tony Carter when I was postgraduate student and he was both Principle and leader of the Fine Art MA at The City & Guilds of London Art School.

Last week I found a used copy which reminded me that I needed to read it – after thirteen years. During that time I have developed both my understanding of Buddhism and a strong daily meditation practice, which I believe puts me in a better position to understand the subtleties of the book.

Tony Carter’s understanding about the connection between Zen, archery, and artistic practice has become apparent to me on page 46 of the text. At this point the author, Eugen Herrigel, has convinced a Zen Master to teach him archery. He has spent a year learning the correct breathing technique for drawing the string of the bow. Having finally understood how to breathe and relax his body he is struggling to let the string of the bow go without jerking the bow, and thus missing the target.

‘You have described only too well’, replied the Master, ‘where the difficulty lies. Do you know why you cannot wait for the shot and why you get out of breath before it has come? The right shot at the right moment does not come because you do not let go of yourself. You do not wait for fulfilment, but brace yourself for failure. So long as that is so, you have no choice but to call forth some thing yourself that ought to happen independently of you, and so long as you call it forth your hand will not open in the right way – like the hand of a child: it does not burst open like the skin of a ripe fruit.’

I had to admit to the Master that this interpretation made me more confused than ever. ‘For ultimately’, I said, ‘I draw the bow and loose the shot in order to hit the target. The drawing is thus a means to an end, and I cannot lose sight of this connection. The child knows nothing of this, but for me the two things cannot be disconnected.’

‘The right art’, cried the Master, ‘is purposeless, aimless! The more obstinately you try to learn how to shoot the arrow for the sake of hitting the goal, the less you will succeed in the one and the further the other will recede. What stands in your way is that you have a much too wilful will. You think that what you do not do yourself does not happen.’

… ‘What must I do, then?’ I asked thoughtfully.

‘You must learn to wait properly.’

‘And how does one learn that?’

‘By letting go of yourself, leaving yourself and everything yours behind you so decisively that nothing more is left of you but a purposeless tension.’

How often do we too ‘brace ourselves for failure’ instead of ‘letting go’ in all aspects of our lives. In relation to artistic practice this notion of ‘letting go’ can be applied such that one is no longer trying to make a picture, or indeed produce a good one. By letting go of the outcome we can feel the brush or pencil and be at one with it in the moment, unhindered, so that the brush is moving without will power, it is automatic like the muscle memory used by sports professionals.

When I learned windsurfing I was told that by breaking down the manoeuvres and practising the movements required I would be training the muscles to remember how to perform the sequences on their own, without the need to think about it. So that when the wind came up and speed together with the correct movement was required the response would be automatic. By letting go of the need to control the equipment the body would feel and respond to the wind directly without requiring any input from the mind.

For the author, the thought of letting go of the string is becoming a block to letting go well. Letting go well would prevent the jerk of the bow and therefore the target would be hit directly. Therefore by not thinking about the goal we would be better able to achieve our goal.

The Master’s comment that ‘you think that what you do not do yourself does not happen’ relates to our ability to let go and to be able to trust. Setting our intention and then letting go of it is essential for manifestation. We need to be able to put our trust in the right outcome happening without straining for it with will power.

I believe that Tony Carter was talking about going with the painting and allowing it to happen without force. Being in the moment, being in the painting, working automatically.

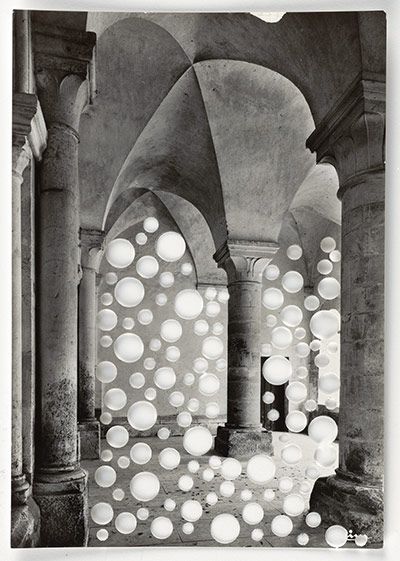

Show Review: Rachel Whiteread

Tate Britain

12 September 2017 – 21 January 2018

The exhibition of Rachel Whiteread’s work currently on at Tate Britain is a real treat because it is the biggest survey of her work ever shown, spanning 30 years of output. This abundance really brings attention to the extensive range of materials she has mastered in her practice during that time.

It features large-scale sculptural works in industrial materials such as plaster, resin, rubber, concrete, and metal alongside smaller works on paper, which are rarely shown publicly and usually only seen in books. Whiteread’s intimate drawings hold a fascination for me because of the variety of mark making techniques she employs; a mixture of varnish, pencil, ink, correction fluid, watercolour, and collage on a range of supports from graph to cartridge paper. She describes her use of correction fluid as being about building up layers, almost like ‘casting a drawing’. By laser-cutting into plywood her drawings have evolved into 3d forms.

Whiteread has said that drawing for her is a core activity that she uses as a visual diary to explore her thoughts and ideas on a daily basis. I feel inspired now to do this myself as a daily practice to let go and see what can come up from my subconscious.

What is particularly interesting for me about this exhibition is the way it brings together her obsession with the domestic, starting with four early sculptures from her first solo show in 1988; a dressing table, a clothes cupboard, the underside of a bed, and a hot-water bottle – which was the starting point for the series of ‘torsos’.

Whiteread became known for her unusual casting technique when she became the first women to win the Turner Prize with ‘House’ in 1993. Traditional casting methods always seek to replicate objects as they are seen, but this ambitious work was a concrete cast of the entire interior of a terraced house in London’s East End.

I have always admired her way of making negative space a solid form because of the way it toys with Freud’s theory of the uncanny by rendering the everyday into something strange, and threatening. As well as exploring the negative space around domestic objects such as tables, beds, bookcases, boxes, and architectural features including stairs, floors, windows, doors, and sheds she has also cast the invisible space inside objects like bottles and mattresses.

These works challenge our perception, creating a conceptual flip that causes us to question our sense of reality.